Parashat Toldot: The Lineage of Yitzchak and Its Meaning

“And these are the descendants of Yitzchak, son of Avraham: Avraham begot Yitzchak.” (Bereshit 25:19).

The Torah introduces Toldot, "descendants," with a seemingly redundant statement: Yitzchak is the son of Avraham, and Avraham begot Yitzchak. Why this repetition? These words emphasize both the continuity and the differences between father and son, offering profound lessons on Yitzchak’s role.

From Descendants to Mission

After Rivka marries Yitzchak and is welcomed into his home, the text shifts to their descendants. The statement “Avraham begot Yitzchak” serves to confirm that Yitzchak was truly Avraham’s son. According to the Midrash, this declaration refutes slanderous claims that Yitzchak was the son of Avimelech, as Sarah gave birth to him after being taken by the king. Hashem dispelled these doubts by making Yitzchak visibly resemble Avraham. As our sages teach, outward appearance reflects character, yet father and son had profoundly different natures.

Yitzchak: A Different Role from Avraham

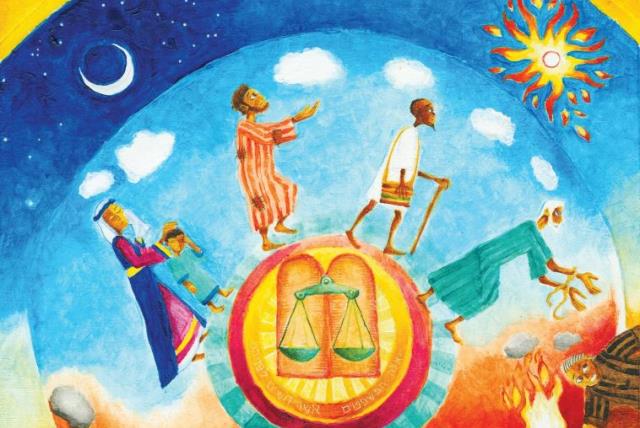

Avraham embodied Chessed, unconditional kindness. He welcomed everyone into his tent, spoke to thousands, and spread Hashem’s teachings indiscriminately. Yitzchak, on the other hand, embodied Gevurah, strength, and discipline. He didn’t aim to reach the entire world but focused on preparing one person—his son Yaakov—to become the father of future generations of the Jewish people.

The difference is also seen in their personalities: Avraham was outgoing and traveled widely, while Yitzchak was introspective and never left Eretz Yisrael. Avraham was a pioneer, opening new paths; Yitzchak consolidated them. His role was to distinguish the holy from the profane, the good from the evil, ensuring the Jewish people followed Yaakov’s example, not Esav’s.

Separating Good from Evil

Yitzchak and Rivka had two sons with vastly different natures: Yaakov, a symbol of virtue, and Esav, a personification of wickedness. Yitzchak’s mission was to draw a clear line between them so that the Jewish people wouldn’t be influenced by opposing tendencies. Although Yitzchak’s life is less detailed in the Torah compared to Avraham’s, it was crucial for this purpose: the people of Israel could not be a mixture of two opposite natures. Representing Gevurah, Yitzchak used the necessary rigor to separate good from evil and nurture holiness.

Balancing Chessed and Gevurah

The Torah reiterates “Avraham begot Yitzchak” to teach that, despite their differences, kindness and discipline are not opposites but complementary. In Jewish life, both must coexist in harmony. Kindness without discipline can lead to permissiveness, while discipline without kindness can devolve into cruelty. Yitzchak and Avraham teach us that approaching Hashem requires a balance of these qualities, reflected in Yaakov, who represents Tiferet (beauty)—the harmony between kindness and justice.

Yitzchak’s Humility: A Quality That Brings Closeness to Hashem

Despite the name Yitzchak meaning “he will laugh,” his life was characterized by reverence for Hashem. As written: “I dwell in the high and holy place, but also with the contrite and humble spirit” (Yeshayahu 57:15). Yitzchak was reverent yet profoundly humble. This reverence didn’t distance him from Hashem; on the contrary, it brought him closer. Chassidut teaches that only those who empty themselves of personal arrogance can become vessels ready to be filled with holiness. Yitzchak’s fear of Hashem made him a devoted servant, intimately connected with the Creator.

Conclusion: A Lesson for Life

Parashat Toldot teaches us that everyone has a unique and irreplaceable role in the world. The differences between Avraham and Yitzchak were not a sign of discontinuity but of completion. Kindness and discipline, while opposite, were both essential to creating a holy and devoted nation. In our daily lives, we can learn from Avraham and Yitzchak to balance these qualities, living with love, strength, and humility in service to Hashem.